It is necessary to explain pain (both acute and chronic) through the biomechanical presentation as part of my practice in osteopathy. Pain can be classified by slight painful disturbances between vertebrae – known as “minor intervertebral painful disturbances” (MIPD) – joint / tissue disorders, and “incorrect repeated or regular posture” (more information about the concept of posture in an other post).

However, due to the rise in neuroscience over the course of a decade, a more elaborate understanding of pain can be gleaned by associating the bio-medical model with the bio-psycho-social model. This can allow us to discover and implement new ways of pain management for our patients.

According to the International Association of the Study of Pain (IASP), pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience linked to a genuine or probable injury. Pain is usually classified as acute or chronic – however, there are also other kinds of pains such as:

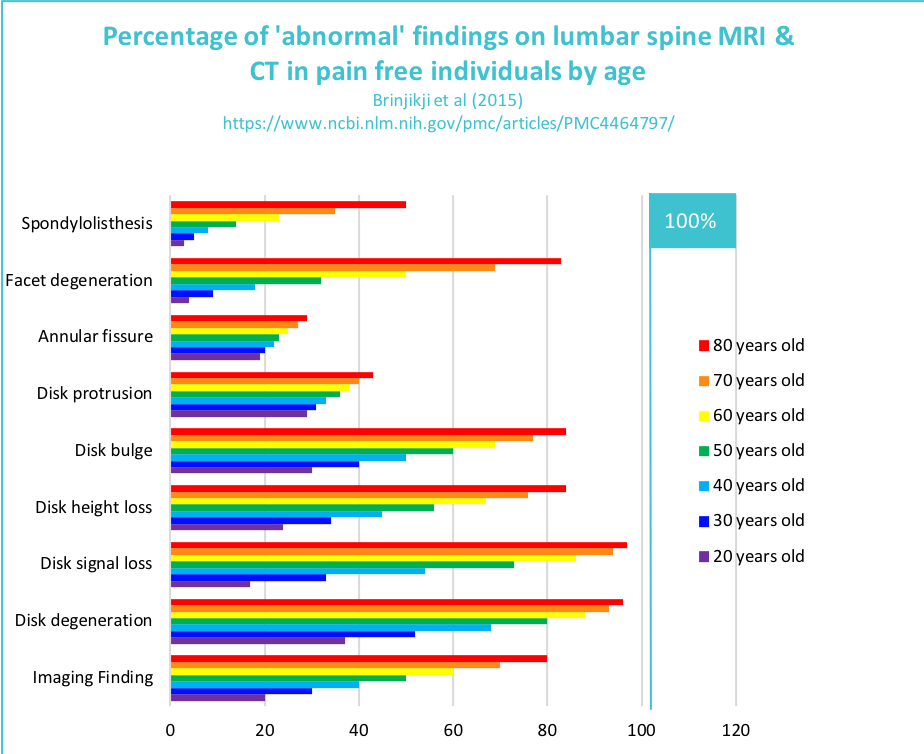

A study conducted by Brinjikji et al. grouped the structural damage on people who displayed no symptoms – as in, who did not experience pain and could be referred to as ‘asymptomatic.’ According to the study, approximately 40% of people around the age of 40 experienced swellings in their discs (disc protrusion). Additionally, 60% of people around the age of 60 experienced lumbar surface osteoarthritis. The study further elaborated that 40% of people over the age of 80 old suffered from the sliding of vertebrae in front of that below – a condition referred to as spondylolisthesis. All in all, they experienced all of these issues without the presence of pain!

Hence, it can be stated that the structural problem does not necessarily lead to pain.

The nociception works to convey an alarm signal from the periphery to the brain in the time of injury or danger. Due to the presence of three different types of sensors (thermal, mechanical, or chemical), the nociceptive impulse transmission is transferred into the electric impulse, arriving opposite the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, and then sent to the brain so that it can be perceived. In the process of traveling along this path, the message can be stopped or facilitated – thus, causing a change in the message when it arrives.

Pain and nociception are not systematically linked. Therefore, it is not necessary for tissue damage and pain to be linked either. The direct cause of pain under a bio-medical model has its limitations, requiring us to approach it with an open mind and expand our thinking.

On the other hand, some pain may remain despite a wound being healed and no tissue damage being identified. The alarm signal – a vital part of one’s survival instincts – and the maintenance of homeostasis can, at times, be aggravated. For example, this occurs with central sensitization syndrome.

Therefore, pain is not always necessarily associated with tissue damage. However, regardless of the origin, the pain itself is very real – hence, one needs to be aware.

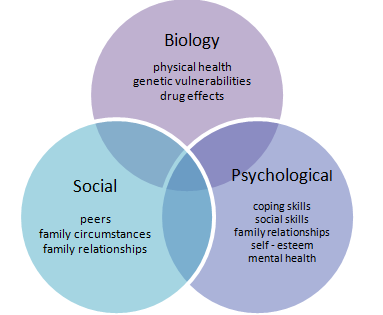

The bio-psycho-social model was introduced by Dr. Engel in 1977. This approach has brought about a prominent change in the areas of health and disease. According to Dr. Engel, both areas of disease and health are the result of psychosocial and biological factors interacting.

According to the International Association of the Study of Pain (IASP), the bio-psycho-social model is a conceptual model that proposes the idea of psychological and social factors being taken into account when studying biological variables in order to gain a deeper understanding of a person’s pathology. The bio-psycho-social model can also be particularly useful in examining musculoskeletal pain.

According to the fear-avoidance model developed by Vlaeyen and Grombez, the appearance of pain can be altered by “an attitude of avoidance, fear of movement, or the spirit of catastrophism.”

For example, phrases such as “My vertebra is displaced,” “My pelvis is shifted,” “Anyway, I have osteoarthritis, it is hereditary,” indicate an individual showcasing various displays of the fear-avoidance model.

There are two behavioral responses in relation to pain:

The wrong interpretation of pain can result in the sense of dread or anxiety. This often is the origin of behaviors seeking a sense of security – however, these behaviors are usually wrongly adjusted and counterproductive. They can encompass negative thinking, showcasing escape and avoidance (reducing or ending social activities, e.g., sports), hypervigilance, high levels of attention, and precaution. An important point to remember is that our pain is controlled by our fears and beliefs.

This model can be qualified by taking charge of the patient as a whole with encouragement in his ability to adapt, the interest of moving and being assured repeatedly about the wellness and vigor of his body.

An illustration by Greg Lehman depicting a cup represents the ability of humans to tolerate bio-psycho-social stresses – if there are too many, the cup overflows. All of us have the ability to adapt to these factors! As practitioners, the best way to support and help our patients often means taking the bio-psycho-social model into consideration.